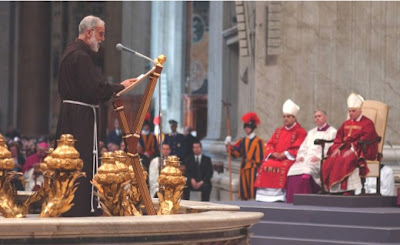

Imagine preaching to the Pope. That is what Capuchin Father Raniero Cantalamessa does. He is preacher of the Pontifical Household, and here is an excerpt from his homily, a meditationfor the third Sunday in Advent, wherein he discusses the idea of Christ's prexistence (cf. Galatians 4, 4-7; Wisdom 9:10, 17;1 Corinthians 8:6; Colossians 1:15-16;1 Corinthians 10:4; Philippians 2:6-7).

"Despite these passages, it must be admitted that in Paul preexistence and incarnation are truths that are still germinating; they have not yet been fully formulated. The reason for this is that the center of interest and the starting point of everything for St. Paul is the paschal mystery, that is, the work, more than the person of the Savior. This is in contrast to St. John, for whom the starting point and the epicenter of attention is precisely the Son's preexistence and incarnation

We have here two different "ways" or routes in the discovery of who Jesus Christ is. One, that of Paul, begins from humanity to reach divinity, from the flesh to reach the Spirit, from the history of Christ to arrive at the preexistence of Christ. The other, that of John, follows the inverse path: It begins from the Word's divinity to arrive at affirming his humanity, from his existence in eternity to descend to his existence in time. Paul's approach makes the resurrection the hinge of the two phases, and John's sees the passage as turning on the incarnation.

These two approaches consolidated in the epoch that followed and gave rise to two models or archetypes and finally to two Christological schools: the Antiochene school influenced by Paul and the Alexandrian school influenced by John. Neither group was aware of choosing between Paul and John; each takes itself to include both. That is undoubtedly true; but it is a fact that the two influences are visible and distinguishable, like two rivers that merge together but are nevertheless identifiable by the different color of their waters.

This difference is reflected, for example, in the different way in which the two schools interpret Christ's kenosis in Philippians 2. From the 2nd and 3rd centuries, even down to modern exegesis, two different readings can be delineated. According to the Alexandrian school the initial subject of the hymn is the Son of God preexistent in the form of God. In this case the kenosis, or "pouring out," would consist in the incarnation, in becoming man. According to the Antiochene school, the sole subject of the hymn, from beginning to end, is the historical Christ, Jesus of Nazareth. In this case the kenosis would consist in the abasement inherent in his becoming a slave, in submitting himself to the passion and death.

The difference between the two schools is not that some follow Paul and others John, but that some interpret John in the light Paul and others Paul in the light of John. The difference is the framework or background perspective that is adopted for illustrating the mystery of Christ. It can be said that the main lines of the Church's dogma and theology have formed in the confrontation of these two schools, which continue to have an impact today.

(See more of Father Cantalamessa's sermons here or check out his site here. )

This difference in perspective is fascinating, considering the discussions surrounding an entry I posted last year, "Understanding Nominalism, Part 1" and discussions resulting from the recent upsurge in enrollment of Reformed students at EBC. a Pentecostal institution. Fr. Cantalamessa has this wise word concerning those sorts of discussions:

3. Beyond the Reformation and Counter-Reformation

I believe it is time to go beyond the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation. What is at stake at the start of the third millennium is no longer the same as at the beginning of the second millennium, when at the heart of Western Christianity the separation took place between Catholics and Protestants.

To give but one example, the problem is no longer that of Luther and of how to liberate man from the sense of guilt that oppresses him, but how to give again to man the true meaning of sin which has been totally lost. What sense does it make to continue to discuss how "justification of the godless comes about," when man is convinced of not having need of any justification and says with pride: "I accuse myself today and I alone can absolve myself, I the man"?[1]

I believe that all the age-old discussions between Catholics and Protestants about faith and works have ended up by making us lose sight of the main point of the Pauline message, often shifting attention from Christ to doctrines on Christ, in practice, from Christ to men. That which the Apostle is anxious above all to affirm in Romans 3 is not that we are justified by faith, but that we are justified by faith in Christ; it is not so much that we are justified by grace, but that we are justified by the grace of Christ. The accent is on Christ, more than on faith and grace.

After having two preceding chapters of the Letter presenting humanity in its universal state of sin and perdition, the Apostle has the incredible courage to proclaim that this situation has now radically changed "through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus," "by one man's obedience" (Romans 3:24; 5:19). The affirmation that this salvation is received by faith, and not by works, is most important, but it comes in the second place, not in the first. The error has been committed of reducing to a school problem, in the interior of Christianity, what for the Apostle was an affirmation of a more vast, cosmic and universal event.

This message of the Apostle on the centrality of Christ is of great importance today. Many factors have lead in fact to put his person in parenthesis today. Christ does not come into question in any of the three liveliest dialogues taking place today between the Church and the world. Not in the dialogue between faith and philosophy, because philosophy is concerned with metaphysical concepts; not of historical reality as is the person of Jesus of Nazareth; not in the dialogue with science, with which one can only discuss the existence or nonexistence of a creator God, of a project of evolution; not, finally, in the interreligious dialogue, where we are concerned with that which religions can do together, in the name of God, for the good of humanity.

Asked about what they believe in, few even among believers answered: I believe that Christ died for my sins and has risen for my justification. And few answered: I believe in the existence of God, in life after death. Yet for Paul, as for the whole of the New Testament, faith that saves is only faith in the death and resurrection of Christ: "if you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved" (Romans 10:9).

I am grateful to Internet Monk for introducing me to Fr. Cantalamessa's sermons and look forward to reading them regularly.

No comments:

Post a Comment