by Fernando Cervantes

from The Tablet: 13/07/2002

(Our summer series of articles aims to help readers embrace leisure without guilt. In the first, a lecturer at Bristol University explains why leisure is both the normal state of humankind and the proper state of scholars.)

I HAVE recently had good news, perhaps the best sort of news that an academic can hope for these days. An award-granting body has looked favourably upon my application: now I have the whole of next year to do research. Cogito, I can declare at last, ergo sum.

Not so long ago this would have happened as a matter of course. Every academic was entitled to such a pause: if the job is to be done properly, it used to be recognised, scholars need leisure for cognition. Only with such leisure can they do the research, book reviews, journal articles, preparation of new courses, and essential thinking about their subject that had been pushed back by teaching, administration, marking, and committees. Hence the sabbatical, from the Hebrew Shabbat, meaning ‘rest’.

How things have changed! The idea that academics need time off to study and think is no longer one that appeals to award-granting bodies. Would I have received my grant if I had told the Board I needed the money for, ahem, leisure? Applications these days are held up to the harsh light of efficiency, productivity and value for money; projects need to be manageable, finishable and, above all, publishable. It is no good reminding the Board of Cardinal Newman’s objection to this utilitarian approach. Utility, he once said, plays against utility, because what is useful today might be utterly useless tomorrow. It is only by giving scholars time for leisure, therefore, that we can expect proper – and ultimately properly useful – scholarship.

But now I’ve got the money, I can say it outside the closet and with relish. Yes, I am a scholar; and therefore a leisure seeker.

Which is what scholar means: from the Greek skhole, “leisure”, which is the root of our word “school”. Here is a concept of leisure hidden from and beyond the reach of our work-obsessed world! To recover its depth of meaning, we must flip back the centuries. It is true that the Greeks, the Romans and our medieval ancestors had deep respect for the dignity of work, but as the means, not the end of life. Like Eden, they saw leisure as lying at the root of things, as the principle and foundation of the higher life. Aristotle said we work in order to be at leisure. Literally translated he said: “we are not-at-leisure so that we can be-at-leisure”. The word he used for work, askhole, means “not-leisure”, and the same is true of Latin. One of its words for work, neg-otium, means “not-leisure” – and this is the great-great-aunt of the modern Spanish and French words for business (and busy-ness): negocio and négoce.

The modern West has turned this on its head. We justify leisure strictly in relation to work. We see it as the idleness necessary for re-charging the batteries, for getting up the energy to go back to work. Too much otium, says our society, and we become self-indulgent and idle; leisure de trop, and we are piggybacking on the poor, industrious taxpayer.

At the root of this attitude lurks the nagging assumption that the truth of anything we know or achieve is in direct proportion to the effort we put into knowing it. Work is good, we are persuaded, because effort is good. What is gained without effort is therefore to be distrusted.

But consider the lilies to realise how outrageously unfounded this assumption is. And not just the lilies: consider us. Our very existence is handed to us without any effort on our part. Do we despise our existence because we didn’t put in the necessary hours? So, too, with our knowledge. Since we believe that we can properly know only what we have reached through conscious, often painful, effort, we tend to refuse to allow ourselves to be given any sort of knowledge. But isn’t the best sort of understanding the one that comes unbidden, unattained, unsought, while having a leisurely bath, for instance, or walking the dog?

Which is why our medieval ancestors sensibly distinguished between discursive thought (ratio) and intuitive thought (intellectus). Ratio abstracts, analyses, refines, deduces, concludes: it is work – often quite hard work. Intellectus does nothing of the kind; it lies back and gets ready. Intellectus is alert but passive; it is open and receptive. It is not idle, but it is emphatically not work.

Or take virtue. We instinctively measure virtuous acts in terms of effort and difficulty. If we find it easy to do good and avoid evil, we do not consider ourselves virtuous. The quintessential Christian virtue of loving one’s enemies, for example, is valued as a virtue precisely because it is a particularly difficult thing to do; and the more difficult we find it the more virtuous it becomes. But this would make little sense if we distinguished between ratio and intellectus. St Thomas Aquinas, said that “the essence of virtue resides more in the good than in the difficulty”. Our medieval ancestors, like the Greeks before them, measured virtue against the standard not of effort but of “the good”. Indeed, said St Thomas, “not everything that is more difficult is necessarily more meritorious. Rather, whatever is more difficult should be so in such a way that it is at the same time a greater good”.

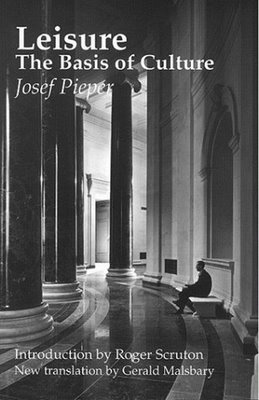

Virtue is not what the modern world understands it to be: as something that allows us to act against our natural inclinations. St Thomas believed the opposite: virtue perfects our actions in such a way that it makes it perfectly possible for us to act rightly, not against but in tune with our natural inclinations. It may be difficult to love a screaming child or an obsequious and self-seeking colleague, for example, but when we pull it off the virtue is not in the effort but in the fact that it miraculously manifests love. And, as St Thomas explained, if the love takes away the difficulty in the act of loving our enemies, that makes it more, not less, meritorious – even though it has little to do with any conscious effort on our part.This is what real leisure is all about. As the German Thomist Joseph Pieper put it nearly six decades ago in Leisure: the Basis of Culture, “the highest realisations of our moral goodness are known to be such precisely in this: that they take place effortlessly because it is of their essence to arise from love”. Just as the greatest virtue is without difficulty, so the highest form of knowledge is received as a free gift. It may well require effort to receive the gift, to tie it down and express it, but the most important aspect of what is known is the part that is achieved without effort.

So how odd it is, this contemporary association of leisure with idleness. For our medieval ancestors it was precisely the lack of leisure – the inability to be at leisure – that was a clear symptom of idleness and sloth. The refusal of leisure was seen as nothing less than the inability to be open and receptive to the world of being, to knowledge-as-gift. They would have identified at once the bitter restlessness of our task-drenched society as acedia, the condition of self-forgetting. In case there is any doubt, St Thomas considered acedia a sin against – what? The work ethic? The joy of production? Holy industry? Not at all! Acedia is a sin against the Third Commandment, the commandment to keep holy the day of rest, the Sabbath.

The modern world of work, marked as it is by absolute activity, is not the reverse of idleness but its symptom. If scholars – among whom, of course, I naturally include Tablet readers – if scholars realised this and had the courage to defend leisure and teach it to their children and their children’s children, we could cease to skulk and whimper when term ends and the precious chance of leisure finally appears. We could stand against the relentless flood of talented and well-trained graduates about to be turned into slothful workaholics. We could proclaim it boldly from the rooftops, far from the madding crowd, loud enough to crack the stone hearts of the work-obsessed. Yes, you can join me in crying, I am a leisure seeker!

No comments:

Post a Comment